Upcycle products have the potential to be one-of-a-kind home accessories.

A designer’s job is to make sure that the model can be converted into a working prototype – a blue print for the manufacturer. However, it is in our nature to measure individuality. Since the 1980s designers have been injecting unique identity “chromosomes” into their products on an industry scale.

High-income earners – which are the industry target – fill the empty space of boredom in their lives by shopping. But possessing the exact same product as everyone else only creates a new kind of boredom. The era of uniform consumerism has ended. Mass products are now being challenged by truly individual designs. Yes, it’s pseudo individualism.

During the 1980s, the concern for environmental damage was no longer exclusive to environmentalists. The call to stop deforestation, environmental pollution, and the green house effect entered into popular culture. Terms such as Eco, Green, and Global Warming were often used, while at the same time the importance of the 3Rs (Reuse – Reduce – Recycle) became ever more apparent.

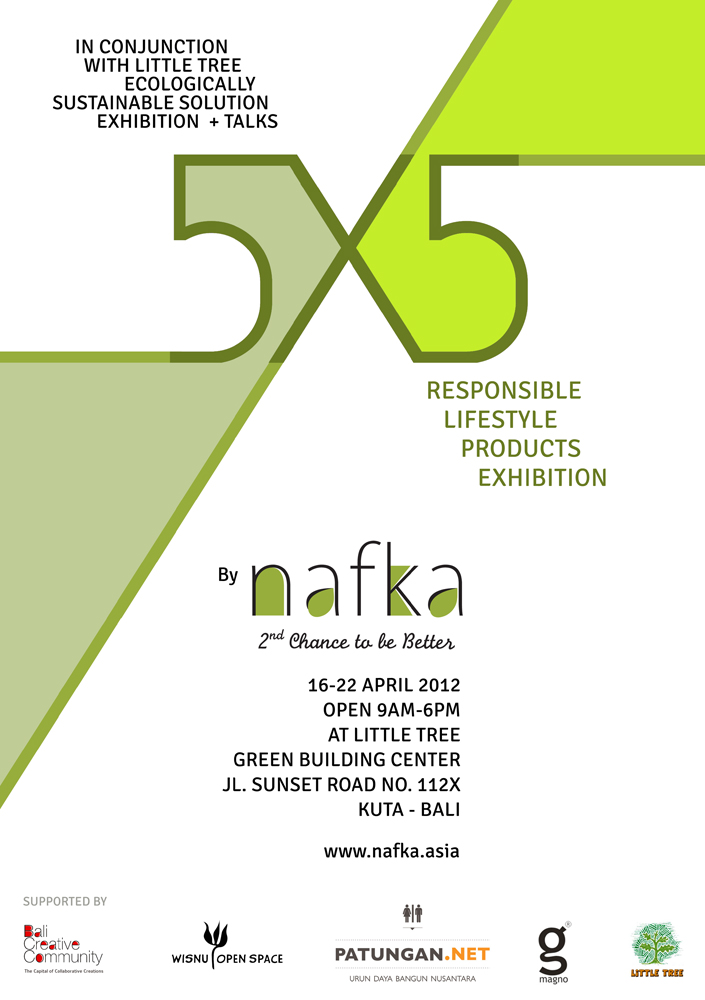

Recycling can sometimes be too expensive and requires a lot of energy. Which is why some people turn to upcycling, which means converting waste or unused materials into something useful, like the products developed by Freitag. In Bali, Nafka initiated a laboratory for creative designers focused on developing responsible lifestyle products. In June 2011, Nafka showed their first exhibit in Denpasar titled Wonderground. Nafka will once again be showing the creations of their designers at the Ecologically Sustainable Solutions Week on April 16–22, 2012 at Little Tree in Kuta, Bali.

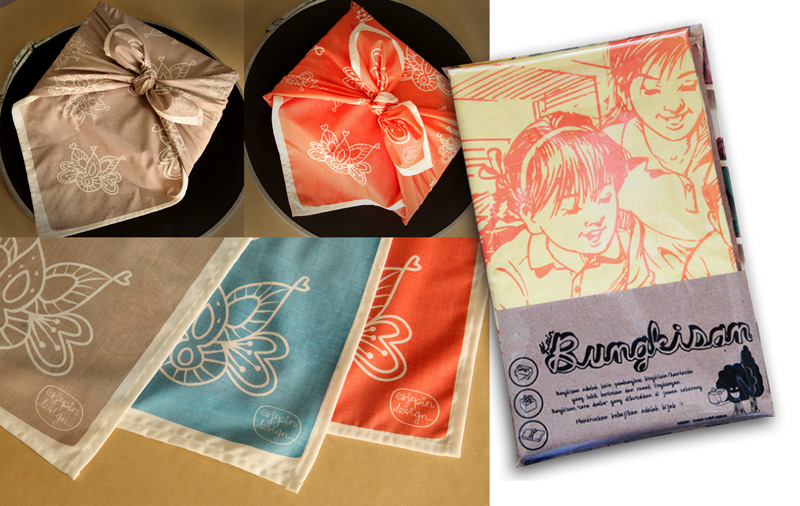

To create designs out of used materials, Nafka designers focus on planning the shapes. Through the process, the used materials can offer unexpected visual surprises. It’s as if looking at a montage or photo collage by artists from the Dadaism era on products such as bags, sofas, room partitions and lamp shades, all made from reclaimed waste or used plastic wrappers. Cut up images, numbers or letters, a build up of colors.

Nafka products seem to fuse the line between art and craft in the shape of everyday accessories. Visually they are attractive. Nafka products are a refreshing surprise in the droll of everyday standard mass-produced products. Nafka products are truly one-of-a-kind.

The products may represent individual expression. But the production process is fueled by a passion for community movement and empowerment. Nafka outsources its production to local handicraft community groups. Handicraft producers, much like other traditional production workers, are marginalized in today’s modern economic distribution routes.

The products may represent individual expression. But the production process is fueled by a passion for community movement and empowerment. Nafka outsources its production to local handicraft community groups. Handicraft producers, much like other traditional production workers, are marginalized in today’s modern economic distribution routes.

In modern sales systems, the middleman marketing the products can be a necessity. When the producer and consumer are too far apart and there is no access between them, the role of the marketer grows ever larger. The role of the middleman in sales is to dictate the price to maximize profits. The producer has little power to sell at a higher, or more profitable price.

This inequality in the marketing stage is only beneficial to the seller and too often exploits the producer. In Bali, these symptoms have long been visible in the industry, for example in the sales of art or crafts. Art shops in Bali have a very high profit margin, sometimes as high as 60 percent on the handicraft products they sell. By the time they are sold, these handicrafts can be expensive, but the amount the producers receive is too far below the selling price.

The partnerships Nafka builds with local handicraft producers follow fair trade standards. In this way they are supporting sustainability, not only the environmental aspects, but also the social aspects.

It takes hard work to follow the principles of fair trade while also successfully conducting business. To make sure the products are not just salable because they are “fair trade” and pulling on heart strings, but because they are of high quality.

If upcycling has it’s own attraction for consumers, could upcycle product hold special economic value? Anyone can take unused material around them and transform it into something new and useful. So, is there still a market for Nafka products? Here the idea of branding comes into play. A product will not just be valued in a utilitarian perspective or at face-value use. Urban residents want to communicate and declare their individuality in the midst of their lonely disoriented lives. Brands provide this.

Brands become a tool for interaction, a celebration of togetherness, even without having to communicate it. A brand is a message in itself.

Pingback: Nafka talks and responsible products presentation | | AkarumputAkarumput