People have a natural desire to master information faster than other creatures. This desire is influenced by the information industry, including the mass media. Hence the battlefield of information technology media is also a race to share a story.

Why do people want to know more and know it before anyone else? Perhaps because, in this way, they feel more powerful than people who are still in the dark. This power does not necessarily achieve inherent and authoritative domination of the subjects of a territory or a country. Power can be achieved within many domains, and it is not always repressive. Knowledge is power.

One form of claiming power over knowledge is by exploring, or at least travelling to foreign places. Recently in Indonesia travel writing has exploded. Recent publications of travel books have lead to a new category on bookstore shelves.

Air travel is no longer an expensive form of transportation in Indonesia—that is what the slogan ‘now everyone can fly’ from one popular budget airline implies. Globally, tourism also continues to develop as an industry. Today, 8 percent of global gross domestic product comes from the travel industry. Where in this world have we not yet explored? Images of remote corners of the earth find their way into mass media and may in time become the most sought-after tourism destinations.

Commercialization of the travel lifestyle creates hyper-realities about new places as treasures as yet to be discovered. However, the impacts of such travel, including environmental degradation, cultural change, and sociological shifts within local communities are often the consequences of the arrival of tourism.

Lately, the concept of responsible travel has been given a lot of attention: Every traveler must be aware of the impacts of his or her visit to a place—both the cultural and ecological impacts. The most responsible travel may, in fact, be to not travel at all; the arrival of a new person in a new place, isn’t just economically beneficial; it can also create larger problems.

The desire to travel and share travel stories has found a modern medium in social networks such as Facebook and Twitter. For example, two days ago, an Indonesian traveler shared photos and stories about her trip to Tibet through her Twitter account.

Her short stories, limited to 140 characters, shared general information about Tibet; but there were errors in the information. She posted that Dalai Lama has not lived in Tibet since 1995. In fact the correct date is 1959, and this spiritual leader has not only “not lived in Tibet” but was forced to flee Tibet and take refuge in Dharamsala, India.

She also shared posts about Potala and Norbulingka palace, along with visually pleasing panoramic photographs. But she forgot to mention how the few remaining monks of Potala are forced to hold positions of cleaners in uniform (not the traditional monk garments). Finally, she reminded followers that the best time to visit Tibet is in August, September, April and May, even though she was there in January.

@tibettruth responded to the posts and stated that the account was a tourist who is spreading the illusion created by Chinese propaganda of a colonized Tibet. @tibettruth is an account for the international movement which supports the reinsitution of Tibet’s independence. The Indonesian tourist replied that her intention was not to spread propaganda, but merely to share what she saw and felt to her friends. This response showed her failure to capture the naked reality about Tibet as a colonized nation. She overlooked the fact that in Lhasa a Chinese military post can be found every 100 meters and miliatary are constantly patrolling the area.

Sometime last year, the photographer Timur Angin also shared his experiences of Tibet through Twitter. Moments after he left Tibet, Timur promoted his plan to form a group tour of Tibet during the country’s best travel season, organized through a photography magazine. His plans were overturned, however, because in 2011 China denied all permits to foreigners to visit the annexed area now known as the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Social networks are designed to allow us to share knowledge; but without indiscrimination. For some travelers, these media are used to propagate a damaging myth of a far-off place.

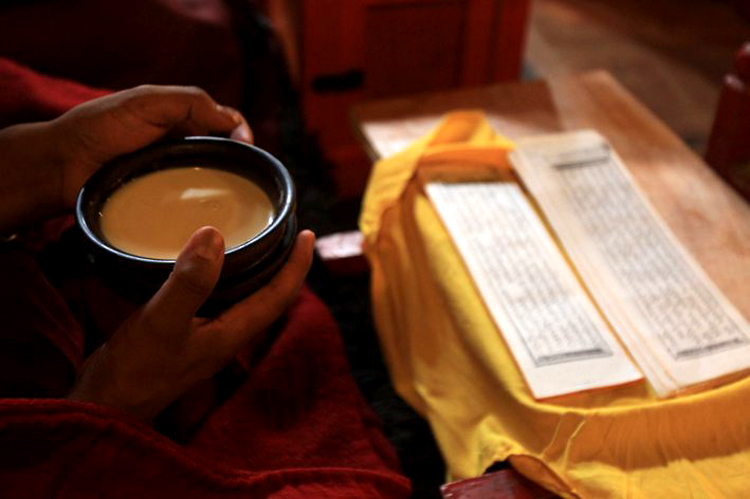

I visited Tibet for 15 days. I experienced Tibet as China’s backyard, used as a location for picnics for Chinese residents, who are enjoying the biggest surge in economic growth in the world. I noted the lines so visible on the faces of exhausted monks at temples or monasteries, whose movements are limited following their rebellion of 2008 against the repressive Chinese military.

I witnessed that the economic sector of Tibet is dominated by people from Mainland China: Almost all souvenir shops and tourist attractions in Lhasa are owned by Chinese. The people of Tibet, who often speak English more fluently than many Chinese, must be content to sell souvenirs from mobile stands in Barkhor. The stand sellers are honest and point out which souvenirs are made by Tibetans and which souvenirs are made in China; not surprisingly, most items are Chinese-made.

I witnessed the train routes, which China claims are part of the infrastructure for the development of Tibet; in actuality they are primarily used as transportation for Chinese going to Tibet. I saw the economic control of China, binding the Tibetan people to poverty. Residents are “mobilized” to an area of annexation—merely a repetition of what China has done previously in Uyghur. In Uyghur, an area with primarily Muslim residents, conditions were extremely repressive, to the point of ethnic cleansing.

I witnessed Chinese military confiscate a Lonely Planet book on Tibet from the backpack of a tourist at the military post along the Nepal border. China banned Lonely Planet books from entering Tibet because their guidebooks include a map showing Tibet in a different color than China and include a photograph of the Dalai Lama, who is exiled in India.

I witnessed Chinese military confiscate a Lonely Planet book on Tibet from the backpack of a tourist at the military post along the Nepal border. China banned Lonely Planet books from entering Tibet because their guidebooks include a map showing Tibet in a different color than China and include a photograph of the Dalai Lama, who is exiled in India.

Even though I made an effort at the beginning of my journey to ensure my own local impact benefited Tibetans (for example, by using a travel agency owned by Tibetans, not a Chinese company), I realized that my trip to Tibet was a mistake. Vacationing in an occupied region is the same as offering foreign exchange to the colonists.

My one pride from Tibet is a t-shirt sporting a Tibetan flag and the inscription “Free Tibet”. This shirt I bought in Kathmandu, Nepal, after convincing the seller to embroider those legendary symbols. “Free Tibet” flags are popular in Nepal, but not one seller is brave enough stock them in their stores. Rather, they are available on order so that store owners avoid the risk of being caught during the Nepalese government sweepings—in this way, the government likes to demonstrate its friendship with China.

During my visit, I wrote a few stories, took thousands of photos and dozens of videos in Tibet. But I did not share these in any portfolio. I don’t want to share my experiences in Tibet to the wider public to encourage other people to visit Tibet.

But I do offer this story I wrote about Tibet, as an appendix to this article.

A prison on the roof of the world

In the plane as we prepared to land, the Tibetan natural landscape transfixed all eyes, and no one blinked. Everest, surrounded by the satellites of lower peaks, appeared like an island in clouds, towering over a cobalt blue sky. The snow blew in gusts, like a flag from a distance.

It was a view you can find in no other country. This country truly is the roof of the world. This land, so grand in its history, is covered by a rich blanket of spiritual practice, devotion to Buddha, invasion, subjugation and oppression. The land is a traveler’s dream. But most travelers must abide by strict rules evening order to enter. Only Chinese tourists enter with ease; they come by the thousands every summer. Tibet is like a playground in China’s backyard.

Accompanied by a tour guide, who contextualizes China’s control over Tibet, the Chinese tourists come to fill the temples and monasteries. They are amazed by what they see, Imagine how much more amazed they would be, if only the Chinese military had not destroyed around 6,000 monasteries during the occupation, beginning in 1951. The religious identity of Tibet was brutally disarmed, and tens of thousands of civilians were killed.

In 1959, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, the living Buddha, left Lhasa in exile to settle in India and continue his struggle to free his homeland.

In some monasteries there are paintings or photographs of all of the Dalai Lamas, with the exception of the 14th. It is forbidden to speak of him or hang his photograph in Tibet. Even tour guides are forbidden to mention him.

In Potala Palace, traditionally the Dalai Lama’s official residence, monks are forbidden to wear their classic red robes. Instead they wear uniforms like maintenance workers and are assigned tasks similar to the care of a museum. Since the monk protest of 2008, which ended in military violence, being a monk is increasingly difficult. The number of monks has decreased dramatically. Before 2008, there were around 600 monks at Potala Palace; now there remain only 200.

Proceeds from the fairly expensive tickets to enter a temple or monastery go to the Chinese government. The temples and monasteries are funded by charitable donations from the people. Not surprising, then that inside the temples we must pay to take photographs, as a way to bring much-needed income to the monastery. In Jokhang Temple, the monks opened a small shop selling “blessed souvenir.” Outside of the monastery, in Bakhor Square, tourists can get almost the exact keepsakes for a much cheaper price.

In Lhasa, tourists are intercepted by Chinese military or police for photographing beggars. China is concerned that images of poverty could ruin their idyllic image of Tibet development. The tallest train rail in the world, running from Qinghai to Lhasa, has been in operation since 2007 and the government boasts it has propelled development in Tibet. But in reality this train rail only makes it easier to transport products from China and mobilize the Chinese military, which have 3 nuclear missile sites and uranium mines in Tibet.

As in Uyghur, China clutches the area through control of the population’s composition. The Han Chinese population continues to increase, and many control business there. To smooth assimilation, Tibetans are forced to study Mandarin in school. No Han is forced to learn the Tibetan language.

Today, no Tibetan can leave the country because they cannot obtain a passport. Until three years ago, many Tibetans fled to Nepal through the Himalayan mountains. Today, however, the Chinese police and military strictly guard these mountains.

While tourists flock to Tibet as a mystical far-off land, the region’s own citizens are prisoners within its borders.

“Tibet under lockdown” photo by Ryan Gauvin via Freetibet.org